Abstracts

Abstracts

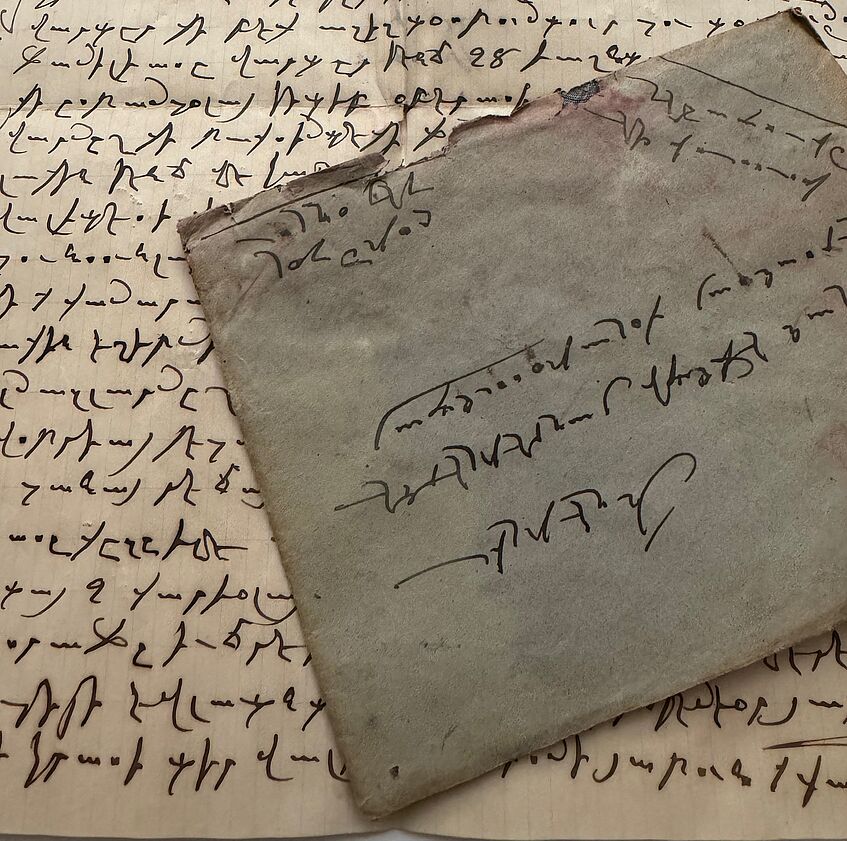

Panel I: Archives, Scripts, and Language

Talin Suciyan (Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich)

The Imperial Language of the Empire: The Use of Armeno-Turkish in Archival Documents

This paper explores the use of Armeno-Turkish in handwritten archival documents from both the Ottoman Archives (BOA) and the Archives of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople (APC). Drawing on materials from diverse regions—including Beyazıt on the border, the center of the eastern provinces Erzurum, the Black Sea region of Çarşamba, and the western part of the empire in Gelibolu—this study highlights the widespread use of Armeno-Turkish across the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century. It examines various document types such as arz-ı mahzar, arzuhal, sened, and istintak, providing insights into their historical content, context, and paleographical characteristics. It also sheds light on the possible reasons for the adoption of Armeno-Turkish in different regions, including the influence of local dialects and social dynamics. Furthermore, the paper considers the wider implications of the use of Turkish in various forms within the institutions of the imperial administration. By addressing the social, historical and linguistic aspects of the use of Armeno-Turkish, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of the imperial administrative practices of the Ottoman Empire.

Orhun Yalçın (Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich)

Script and Governance: Armeno-Turkish and Diplomacy in the Ottoman Ministry of Foreign Affairs

This paper examines the use of Armeno-Turkish through an analysis of mid-19th-century diplomatic correspondence based on Ottoman Archival sources. Sent from Vienna, consular officer Kasbar Manas corresponds with the Ottoman Ministry of Foreign Affairs for the delivery of a carriage. The case provides insights into the intersection of language, script, and diplomacy within the imperial framework and how this language form facilitated the official correspondence. By focusing on how Ottoman Turkish terminology—particularly in bureaucratic and financial contexts—was rendered in Armenian script, this study illustrates the linguistic hybridity in administrative practices of the period. By exploring the orthographic adaptation of Ottoman Turkish vocabulary into Armeno-Turkish, the research illuminates the dynamic interplay between language and imperial governance. From a broader perspective, this study reflects on non-Ottoman archival sources located in the Ottoman Archives in terms of their way their categorization, translation and service to the users. This paper contributes to the growing body of scholarship on the role of the languages and scripts of non-Muslim communities in Ottoman bureaucratic and diplomatic history, offering fresh perspectives on imperial governance, social diversity, as well as multi-lingual practices of the empire.

Flora Ghazaryan-Abdin (Central European University, Vienna)

“The Richest and Most Favoured Rayahs of the Sultan”: The Armeno-Turkish Accounts of the 1819 Düzoğlu Execution in Ottoman Istanbul

On October 19, 1819 Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II (r. 1808-1839) instructed his grand vizier to execute four Düzoğlu brothers who served in the Imperial Mint as well as royal jewellers. The execution of the Düzoğlu family, a prominent Catholic Armenian dynasty, is a contentious historical event marked my multiple interpretations across Armenian sectarian lines. Furthermore, it happened in an internally and externally turbulent period for Ottoman politics, adding international dimension to it. My proposed paper investigates the divergent narratives, and notable alternations present in Armeno-Turkish versions of the Ottoman execution order, offering insights into political and sectarian tensions that shaped this family’s downfall. Official Ottoman records framed this execution as a punitive measure justified by legal transgressions tied to financial irregularities within the Imperial Mint. However, Armenian accounts, with Armeno-Turkish copies of the state orders, present a spectrum of interpretations, each with distinct biases and political motivations. As such, this paper’s central question is how did different Armenian factions interpret and reframe the Düzoğlu execution, and what does this reveal about geopolitical, social, economic, and religious tensions of early nineteenth-century Ottoman Istanbul?

The varied perspectives of Armenian accounts coalesce around four major interpretative “scenarios,” each documented by different Armenian denominational faction: the Düzoğlu family’s own autobiography, writings by Ghukas Oghulukian from the Vienna Mekhitarist Congregation, accounts from Venetian Mekhitarist monks, and narratives provided by Apostolic Armenian sources. Each “scenario” reflects the affiliations and objectives of its authors, creating conflicting renditions of the family’s fate. For instance, some versions present the execution as a culmination of a personal vendetta orchestrated by Ottoman Muslim state officials and their Jewish moneylenders, others present the events as an episode in sectarian strives, where the Düzoğlu’s became casualties of intra-Christian antagonism and political maneuvering.

Through a close examination of varied Armeno-Turkish copies of the Ottoman order from different collections (Matenadaran Manuscript Institute, Vienna and Venice Mekhitarist Congregations, Istanbul’s Armenian Patriarchate, and Etchmiadzin), this paper elucidates the ways each faction adapted, omitted, or added elements to serve their narrative purposes. This approach demonstrates how sectarian identities and geopolitical alliances in early nineteenth-century Istanbul influenced both the historical record and collective memory. Additionally, this framework facilitates navigating the complexities of archival sources, recognizing the layered textures and silences within historical record.[1] By mapping these additions and omissions, my paper advances a framework for understanding how competing narratives can shape and distort the legacy of complex political events within and beyond the Armenian community.

Naira Poghosyan (Yerevan State University)

Upholding Toros Azatyan’s (1898–1955) Armeno-Turkish Literary Archive

The practice of collecting books, manuscripts and, more broadly, literary archives, could be traced back to Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. In the course of history, the practice of amassing books has become the subject of socio-cultural scholarly discourse, resulting in the emergence of the term "bibliophilia" as well as its varieties like bibliomania, bibliophagy etc. In a broad sense, the significant role of bibliophiles in the preservation and dissemination of the literary works is difficult to overestimate. Their collections can become the subject of scholarly research not merely from the literary perspective, but also from social, cultural, and even economic standpoints. This study focuses on the Armenian-Turkish segment of the literary archive of the Istanbul-Armenian philologist, poet, editor and public figure Toros Azatyan (1898-1955). T. Azatyan's multilingual archive (comprising more then 15000 Armenian, Ottoman, Latin Turkish, Arabic, English, French printed and written materials) was transferred to Soviet Armenia in 1957, after his death with the assistance of his wife Shushanik Azatyan, brother Vahan Azatyan and Istanbul Armenian intellectuals. It is currently housed in the Armenian Museum of Literature and Art as well as in the Depository of Ancient Manuscripts Matenadaran. The collection, which includes the plethora of manuscripts, books, newspapers letters, notebooks was amassed by Azatyan throughout his life all over Turkey. The Armeno-Turkish section encompasses manuscript collections, printed samples, personal handwritings, periodicals. Some materials, such as the third issue of satirical newspaper “Zvarchakhos”, are unique and not found in other collections that are currently known to us. Borrowing the microhistorical concept of using smaller units to illustrate broader historical trends we will study Azatyan’s Armeno-Turkish collection to shed light on two different socio-cultural aspects. Initially, a qualitative investigation of the archive would help to identify whether there are “utilisation areas or consumers” of the Armeno-Turkish in Istanbul and the broader Ottoman Empire that have been overlooked by the existing academic research. In this context, the strategies and reasons for choosing the Armeno-Turkish as a medium of everyday communication would be elucidated on two temporal platforms: 1) materials preserved and collected from the 19th century 2) early decades of the Republic of Turkey when Armeno-Turkish was used directly by Azatyan and his contemporaries. Furthermore, this investigation would contribute to understanding the peculiarities and mechanisms of preservation and transfer of Armeno-Turkish literary works as well as ego documents under the challenging circumstances of Ottoman Empire’s decline, transition of political regime and shifts in the frontiers. Secondly, given that the archive comprises a greater number of literary works and periodicals published during 19th century throughout the Empire than personal papers, the examination of these materials would facilitate the reconstruction of the imperial capital’s and periphery’s literary portrait and tracing the role of Armeno-Turkish in shaping the tastes of the Ottoman “reading class”. The data gathered, analyzed and compared during our research will finally assist to unfold hidden layers of T. Azatyan’s archive and gain insights into the cultural consumption of Armeno-Turkish.

Panel II: History and Historiography

Lusine Khachatryan (Yerevan State University)

Armenian-Script Turkish Medical Manuscripts and the Fusion of Medicine and Tradition in the 18th–19th Centuries

This study explores a selection of 18th-19th century Armenian-script Turkish selected manuscripts that reveal significant medical developments of their time, coinciding with the Ottoman Empire's adoption of European medical knowledge. It is noteworthy that the turning period of the appropriation of European medical knowledge can be observed in the second half of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century in the Ottoman Empire. Under the scope of this research, I will illustrate the transitional phase in Ottoman medicine, where established Islamic medical traditions coexisted with and gradually adapted to European innovations. The examined manuscripts represent a critical but underexamined facet of Ottoman medical and cultural history. Conducting comprehensive studies and comparative analyses with equivalent originals could shed light on their role in cross-cultural knowledge exchange and the evolution of medical knowledge in the Ottoman period. The manuscript Ms. 9711 (dated 1768) exemplifies this shift as it is a direct translation from Latin by the “renowned Spanish physician Juliano," commissioned by an Armenian doctor named Karapet from Istanbul. Notably, this translation was edited by a clergyman, Manvel, and lauded for being bilingual—thereby broadening its accessibility. In addition to structured translations like Ms. 9711, other manuscripts in this collection vary greatly in form and content. For instance, Ms. 10563 contains medical recipes written in verse, reflecting oral transmission traditions, while Ms. 10661 blends Arabic-Islamic traditional medicine with Latin-inspired prescriptions. These stylistic and linguistic variations, including the use of Armenian-script Latin and mixed Armenian-Turkish, highlight the dynamic interplay of cultural and linguistic influences. By including supplementary bilingual dictionaries and detailed annotations, the authors ensured the accessibility of these works to both Armenian-speaking and Turkish-speaking members of the Armenian community. Records explicitly emphasized the benefit of writing in two languages, aiming to bridge linguistic divides within the multicultural Ottoman Empire. Looking through the manuscripts that reveal a rich interplay between innovation and tradition, I will discuss how these works combined modern pharmaceutical methods with older practices, as seen in texts offering charms against the plague and references to classical figures like Galliano, and how “new European” knowledge was appropriated and how the ancient traditions continued to be dominant and influential. By examining these manuscripts, we gain a deeper understanding of how the Armenian community and Ottoman society at large engaged with and contributed to the medical and cultural innovations of their time.

Gayane Ayvazyan (Harvard University)

The First Translation of Armenian History by Movses Khorenatsi into Armeno-Turkish

In the 17th century, Istanbul Armenian intellectual Eremia Chelebi Komurjian significantly reshaped previously known geographical boundaries and thematic trends of Armeno-Turkish literature. First, Istanbul became a preeminent center of a long-lasting writing tradition in Armeno-Turkish. Second, alongside predominantly religious texts and songbooks in Armeno-Turkish, Komurjian introduced new genres to the field by translating regionally as well as internationally famous narrations of his time and writing many letters, cevapnâmes, treatises, and other polemical texts addressed mostly to the Jewish and Greek authorities. According to Armenian official historiography, the first translation of Armenian History by Movses Khorenatsi was made in Latin by H. Brenner in Stockholm in 1733. Actually, the first translation of the History appeared in Armeno-Turkish by Eremia Komurjian in Istanbul in the second half of the 17th century. The above-mentioned translation by Komurjian remains unpublished and is held in manuscript form (MS N411) at the Venice Mekhitarist library. By introducing the manuscript in his History of Armenia in 1786, Mekhitarist Father Mikael Chamchian states that the translation was done by the request of Ottoman Muslim intellectuals. Aram Ter-Ghevondyan, a researcher at the Institute of Oriental Studies in Soviet Armenia, develops Chamchian’s argument, by identifying that the translation was used in Câmiü’d-Düvel by Müneccimbaşı Ahmed Dede. However, Ter-Ghevondyan derives his observations from secondary, rather than primary sources. First of all, he did not read the History in Eremia’s translation into Armeno-Turkish, as well as was not able to have access to Câmiü’d-Düvel originally written in Arabic. Instead, he used the translations of Câmiü’d-Düvel into Turkish by Nedim and into Armenian by Galust Tirakian, as well as a Brief Questionnaire in Armenian, a distinct work addressing some questions of Armenian history, written by Komurjian. The arguments made by Chamchian and Ter-Ghevondyan were uncritically approved and repeated by other scholars. In 2023, I had a long-awaited access to the manuscript of Armenian History in Armeno-Turkish by Eremia Chelebi. This conference would be a great opportunity to present my ongoing research on this translation and get feedback to further develop my project. First, the intertextual comparison between the above-mentioned versions of Câmiü’d-Düvel and its supposed source in Armeno-Turkish by Komurjian significantly reshapes previously accepted arguments on this question. Second, by situating this translation in the context of Eremia Komurjian’s historiography and his social and political affiliations, the purpose of this translation seems to be more related to the shifts and trajectories on early modern Armenian political landscape rather than Ottoman interest in ancient Armenian history. Thus, alongside the intertextual research, my paper will explore the social and political context in which Eremia translated Armenian History by Movses Khorenatsi into Armeno-Turkish, by answering why this History, which I would call the Bible of modern Armenian identity, was translated into Armeno-Turkish in seventeenth century Istanbul.

Johann Strauss (University of Strasbourg)

Vartan Pasha’s "History of Napoleon Bonaparte"

Among Ottoman Napoleonica, the Tarixi Napoleon Bonaparte imperatoru ahalii Fransa by Vartan Pasha (Hovsep Vartanian (Vartanyan, 1815-1879) is without doubt the most impressive example. At the same time, it is also one of the most amazing realizations of Armeno-Turkish writing in the 19th Century. This work of nearly 1500 pages (2 vol., Istanbul, 1855-1856) printed by Mühendisian, was published in a language and a script accessible only to the relatively limited audience of Turkish speaking, in particular Catholic, Armenians. Its fame transcended however the borders of this community and the Armeno-Turkish text was some years later followed by an Ottoman-Turkish version in Arabic script, considerably reduced in size (Târih-i Napolyon Bonaparte ; 2 vol., Istanbul, 1861 – 1868). Both versions remained unfinished. The Tarix appeared at the time of the Crimean War. It was compiled, according to the author, from some twenty works by « famous and respectable French and English writers » (Fransız ve İngiliz meşhur ve muteber müellifler tevarixinden bilintixab), who are occasionally also mentioned in the footnotes. The paper not only intends to give an overview of this monumental work. It also aims to shed light on the motives of the author (including those for his choice of the language!), Vartan Pasha´s use of the sources and his method in translating documents. A particular interesting aspect is the language of the Tarix, the rendering of modern concepts, political terminology etc., at a period where standardization had not yet been achieved in Ottoman Turkish. The differences between the versions in two scripts are equally revealing. In particular, the comparison allows us to highlight the quite considerable differences that existed between Armenian and Ottoman Turkish print culture in the 19th Century.

Yaşar Tolga Cora (Boğaziçi University)

An Armeno-Turkish Source for Labour History: The Culfa Epic (1899)

Historians of the ordinary people and groups such as workers and artisans often complain about the lack of sources which present the voices of these historical actors. It is true that most of the sources on these groups are not written by them; state officials or foreign observers produce many sources and their writings carry various levels of hierarchies of power. Historians try to overcome the problem by analyzing sources created by the ordinary people such as petitions. Although this reduces the problem to some extent, the actors themselves do not usually create these sources either; they are written down by an intermediary (a clerk, a court employee, etc.) and they, too, use the dominant discourses of the period while addressing a higher authority. Here, this deficiency can be remedied by using the opportunities offered by literature, which is the Siamese twin of social sciences, as Zygmunt Bauman puts it. Especially oral narratives, although they are few in number, have the potential to redress this deficiency to some extent and open up new fields of study. In this presentation I will examine the “Culfa Epic” written in epic (destan) form in Turkish in Armenian letters by Krikor Kalustyan, in terms of its potential contribution to labor and social history. Kalutsyan was an Armenian from Maraş and included the epic in his memory-book on that town. The poem is written in the local Maraş dialect Turkish spoken but in the Armenian alphabet and consists of 51 quatrains. Kalustyan wrote the epic while working in an alaca (local fabric) workshop in Adana in the summer of 1899. As both Turgut Kut’s previous studies and Ayhan Aktar’s recent study have shown, epics continued to be produced in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, within the Armenian communities in Anatolia and after the Genocide in the diaspora. As will be examined in the example of the Culfa Epic, such works have the potential to make original contributions to the study of the ordinary people as they provide information on the mundane aspects of their daily lives. Although, it is very difficult to reach the individual stories of workers, as Sherry Vater has also stated in her study on the alaca journeymen in Damascus, the “Julfa Epic” provides us with new ideas on subjects that are rarely examined in labor history studies, such as the financial difficulties of a worker working at an alaca workshop his family life, his relationship with his loom, his religious beliefs and expectations. Secondly, as Jacques Ranciere, who studied worker-poets in nineteenth-century France, has shown, such texts provide historians with opportunities to understand the transitions between subjectivity and social groups such as community and class that have similar experiences, as well as the areas of conflict between them.

Panel III: Multilingualism and Translation

Anna Ohanjanyan (Mesrop Mashtots Research Institute of Ancient Manuscripts, Yerevan)

Encountering Languages: Armeno-Greek, Armeno-Latin, and Armeno-Turkish in the Ottoman Armenian Apologetic and Polemical Literature: The Case of Gēorg Mkhlayim Ōghlu (1681/85–1758)

The Armeno-Turkish (Turkish written in Armenian script) was one of the primary written languages used within the Armenian communities in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries of the Ottoman Empire. Less commonly known is that on rare occasions, Armeno-Greek (Greek written in Armenian script) and Armeno-Latin (Latin written in Armenian script) also appeared in apologetic and polemical literature of the time since the liturgical as well as polemical/apologetical texts in early modern period served as venues of contact and interaction, mirroring multilingual, multicultural and multireligious environment of the Ottoman Empire. This paper examines the multilingual landscape of Ottoman-Armenian apologetic literature from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, with a particular focus on the works of Constantinople-based Armenian theologian and patriarchal polemicist Gēorg Mkhlayim Ōghlu. His treatise, titled Catholicity of the Followers of Lusaworich’s Faith (Katʻoghikēutʻiwn lusaworchʻadawanchʻatsʻ), has survived in two copies: one in the Mekhitarist Library in Vienna (W1243) and another in the Matenadaran in Yerevan (M6458). This work, written in Classical Armenian (Grabar), incorporates pages and passages in Armeno-Turkish, Armeno-Greek, and Armeno-Latin. These languages, all written in Armenian script, were strategically included into the text to support specific arguments, reflecting the Ottoman Empire’s multilingual, multi-religious setting and the intense theological/ confessional debates within Armenian communities and confession-building processes of the period. As a polemicist, Mkhlayim Ōghlu frequently employed Armeno-Turkish in his writings to spread his ideas. He turned to Armeno-Greek and Armeno-Latin when he needed to reference Greek or Latin sources. While Greek and Latin were comprehensible to Ottoman-Armenian literati, their scripts were not commonly readable. The paper’s core research questions are: 1. When and why does Mkhlayim Ōghlu turn to Armeno-Turkish, Armeno-Greek, or Armeno-Latin in his writings? 2. How do these choices shape his arguments and resonate with his intended audience? 3. What do these multilingual practices reveal about the broader religious and cultural environment of his time? Using a combined quantitative and qualitative approach, the paper compares passages in Armeno Turkish from Catholicity with those in Ōghlu’s other works to identify patterns and intentions behind his shifts from Armenian to these other languages. Additionally, it analyzes syntax and linguistic nuances to understand how Armeno-Turkish, Armeno-Greek, and Armeno-Latin each contribute to his theological arguments. Ultimately, the paper illustrates how Ōghlu’s use of language was more than just a stylistic choice; it was a way to navigate complex cultural and religious dynamics, making his arguments more accessible and persuasive to his audience. By exploring these multilingual practices, the study reveals the nuanced role of language in shaping religious identities and confessional boundaries in the Ottoman Empire.

Hasmik Kirakosyan (Mesrop Mashtots Research Institute of Ancient Manuscripts, Yerevan)

Transforming Adab in Another Light and Script: Tracing the Armeno-Turkish Translations/ Tradaptations of the Ṭūṭīnāme ("Tales of a Parrot")

The Ṭūṭīnāme, a captivating narrative framed as a series of parables, allegories, and moral tales, has transcended linguistic and transcultural boundaries, resonating with audiences far beyond its Indian origins and Persian translations. The translation variants of the well-known work into (Ottoman) Turkish facilitated its accessibility to a wider readership, thereby contributing to the dissemination of Persian literary traditions throughout the Ottoman Empire over time. In my presentation, rather than delving into the history of Persian-Turkish translations and their reception, I aim to explore two transcription texts of the renowned tale in Armenian script Turkish that are housed in the Matenadaran. The first manuscript, MS 6657 "Dudi name," originating from the seventeenth century, contains 32 tales and the second manuscript, included in Miscellany 10605 (presumably from the eighteenth century), comprises 41 stories. Through close reading of these texts and comparative analysis of the Persian and Ottoman Turkish manuscript and printed versions, I posit that the transcription texts represent tradaptations rather than direct translations from the Ottoman Turkish source. The unknown translators-scribes endeavored to convey the instructive nature of the Ṭūṭīnāme stories, fostering a culture of adab, and opted for an accessible approach by employing Turkish vernacular language for ease of comprehension. The use of vernacular language in the translation text raises an intriguing question: Could the Armeno-Turkish version represent yet another distinct translation variant, separate from Ottoman (Turkish) translations? Thus my presentation unfolds with a dual focus: Firstly, I delve into the motivations driving the translator-authors of the Armeno-Turkish versions of "Tutiname." Secondly, based on the analysis of the manuscripts, particularly the Miscellany, I delve into the question of reception, illuminating how these adaptations were perceived within their respective transcultural contexts.

Gunvald Axner Ims (University of South-Eastern Norway)

John Bunyan’s A Pilgrim’s Progress in Translation

At the Uppsala University Library there are two late 19th century translations to Turkish of the 1678–84 English classic “A Pilgrim’s Progress” by John Bunyan. As Laurent Mignon underlines in his 2014 article “A Pilgrim’s Progress: Armenian and Kurdish Literatures in Turkish and the Rewriting of Literary History”, Bunyan’s work is one of the most translated literary works in Turkish. Mignon lists eight different Turkish translations of it, of which four were published in the 19th century. Three of these are in Armenian script, while one is in Greek script. In comparison, the first Ottoman Turkish translation in Persio-Arabic script was printed in 1905. The first of these translations available at Uppsala University is listed as “Hıristiyan yolculuğu: yani, Müminin helak şehrinden semavî şehre seyahetı”. This is an Armeno-Turkish text published 1881 at A. Hagop Boyacıyan printing press in Istanbul and known to be a revised edition an 1864 Armeno-Turkish translation. The other translation is a Karamanlidic book, i.e. printed in Greek script, at the same press. It was published in 1879 and is listed in the catalogue of the Uppsala University Library as “Hrıstiyan yolcılığı”. As Mignon points out, these Bunyan translations have been mostly neglected in literary research and history. One explanation for this exclusion has been that Armeno-Turkish and Karamanlidic texts have not been counted as Ottoman literature. Due to the lack of research in literature like this, many questions remain unanswered, for instance: How similar are the various translations to each other, and to the original? Given the original work’s status as a missionary text with Protestant message, how are Biblical references and religious language in the translations, which are targeting (mostly) non-Protestant groups? In my preliminary research, I’ll focus on the 1881 Armeno-Turkish translation, and ask what this text can tell us today about how cultural plurality was shaping Turkish literature in the late Ottoman Empire. With shaping of literature, I mean both the outer shaping of texts in certain genres and alphabets, and the forming of more inherent aspects of them, such as the genres they are written into, what typological patterns they display, and what realities they portray. My project would involve the transcription into the Latin script of at least parts of the Armeno-Turkish text, and a comparison of this text to the English original. It will evolve with a parallel transcription of the Karamanlidic text in order to compare the different versions of the original English text. Combining narratological theory with translation studies, it could be of interest to analyze how the Armeno-Turkish translator positions the narrator and main character in relation to their imagined readers. What degrees of proximity and distance between the imagined readers and the topic of the books? Since translation always involves a transition from one cultural context to another, I expect to see choices that the translator has made in order to reach a new readership.

Betül Bakırcı (Aras Publisher, Istanbul)

Re-reading Akabi Hikâyesi After 173 Years

While the historical development of the Turkish language has typically focused on its written form in the Latin and Arabic scripts, Turkish has, over time, been written using various alphabets by different communities. In this context, Turkish texts written and printed in Armenian script have formed a significant literary and cultural heritage from the 14th century to the first half of the 20th century, influenced by cultural, political, and social factors. These texts are not confined to literature alone; the use of Armenian script also reflects the interactions of Armenians with each other and their relationships with other cultures, providing valuable historical insight. Especially after the 19th century, with the growth of printed works, Turkish written in Armenian script evolved into a kind of “publishing language” becoming widely followed by other communities within the Ottoman Empire. For instance, in Istanbul alone, 85 printing houses published Turkish books in Armenian script and nearly 50 newspapers and journals were published in Turkish using Armenian script. These figures highlight the significant role of this writing system in the press and literary worlds of the Ottoman Empire, offering a deeper understanding of the cultural influence of Turkish written in Armenian script and the social development of Ottoman Armenians. At this juncture, the 1851 work Akabi Hikâyesi holds particular significance. Written by journalist, author and translator Hovsep Vartanyan, this work is the first Turkish novel written within the borders of the Ottoman Empire. Vartanyan intricately explores the cultural dynamics of the Armenian community of his time in Istanbul, shaping the novel’s content across a wide spectrum—from social class differences to attitudes toward entertainment, and from daily life habits to the nuances of everyday existence. By narrating the love story of a Catholic Armenian and an Apostolic Armenian, Vartanyan also presents an early modern attempt at the novel genre. However, in the context of Turkish literary history, Taaşşuk-ı Talat ve Fitnat, with its Arabic-script version is typically considered the first Turkish novel, thereby overshadowing Akabi Hikâyesi, which was written nearly 21 years earlier. This omission has hindered a comprehensive understanding and accurate evaluation of Turkish literary history.

173 years later, Akabi Hikâyesi has been reintroduced to Turkish readers by Aras Publishing, which not only preserves its literary value but also renews the significance of Armeno-Turkish script in the context of literary history. The first Armenian edition of the novel was published in 1954, followed by various editions over the years. In 1991, Andreas Tietze was the first to transliterate it into Latin script. The edition published by Aras presents the original text along with detailed annotations. The translation was carried out with great care, considering both the historical context of the text and the linguistic features of the period. Additionally, to facilitate accessibility for modern Turkish readers, this edition was prepared with annotations and includes a vocabulary glossary for the readers. In this presentation, I will first discuss the transformation of Armeno-Turkish literature in the 19th century, the political significance of Akabi Hikâyesi, and its influence on Ottoman literature as a modern attempt at the novel. Following that, I will share the transcription process of the novel, along with the methods employed in this process. Finally, I will address the books published by Aras Publishing in the field of Armeno-Turkish texts, present the translation methods used, and explore the publisher’s program for Armeno-Turkish literature. Akabi Hikâyesi not only holds literary value but also sheds light on the intersections of Turkish and Armenian literature. Through its unique position in Ottoman literary history, it bridges two distinct linguistic and cultural traditions, offering valuable insights into the shared social and political contexts of the time. The publication of Akabi Hikâyesi after 173 years not only revives a significant piece of Ottoman literary heritage but also opens up new avenues for future research into the underexplored aspects of Turkish and Armenian literary traditions.

Panel IV: Preserving Armenian Cultural Heritage in Vienna and Armenia

Tigran Zargaryan (Fundamental Scientifi c Library of the National Academy of Sciences of RA)

Digital Library of Armenogram Turkish Printed Materials: Resource Locator and Research Starting Point

Armenogram Turkish (Armeno-Turkish) books and periodicals represent a unique aspect of Armenian literary tradition. Over 2,000 Armeno-Turkish books were printed from the 18th century until the 1960s, beginning with the first Armeno-Turkish book, “ԴՈՒՌՆ ՔԵՐԱԿԱՆՈՒԹԵԱՆ”, published by Mkhitar Sebastatsi in Venice in 1727. These books were produced in around 50 cities and over 200 printing houses worldwide. Additionally, approximately 120 Armeno-Turkish periodicals were also published, primarily in the late 19th century, in cities with large Armenian populations. These publications are crucial for understanding the linguistic and cultural exchanges between Armenian and Turkish communities during that period. These publications, which are scattered across the globe, warrant closer examination by specialists, including librarians, digital humanitarians, and linguists. The fragile nature of these materials is further threatened by climatic factors, with fungal damage to paper being a significant concern. Therefore, the long-term preservation of these resources is becoming increasingly critical.

The Fundamental Scientific Library of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) of Armenia has over 20 years of experience utilizing Free/Open Source Software in libraries and implementing Open Access publishing models within NAS institutions. As a leading research institution in preparing bibliographies, long term preservation through digitization and digital library development in Armenia, our primary goal is to create a subject-oriented digital library for Armenogram Turkish printed materials. This digital library will feature bibliographic descriptions and, where available, full-text materials. Relevant hyperlinks will direct researchers to the websites of institutions that preserve these resources, and Optical Character Recognition will be applied to digital copies whenever feasible. Recent projects have laid a strong foundation for this initiative. Notably, we published a bibliography of the Armenian book collection at the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality Taksim Atatürk Library in 2022, which covers 119 Armenogram Turkish books, including 15 newly discovered titles (the database is created). We are also conducting ongoing bibliographic research at the Ormanean Library of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, with a bibliography forthcoming. Additionally, we completed the first stage of the project “Digitized Collections of Armenian Newspapers and Periodicals from the Mekhitarist Monastery of Vienna”, making 20 Armenogram Turkish newspapers available in an Open Access repository. Current collaborations with the Mekhitarist Congregation in Venice and the development of the subject-oriented digital library "Armenian Book" covering the period from 1512 to 1920 (in four sequences), further support this project. Our involvement in the “Armenian Book” and “Union Catalog of Armenian Continuing Resources” projects, managed by the National Library of Armenia, adds additional expertise and support. We are planning to start collaboration with the "MEKHITAR" project.

The project outcomes are threefold: (i) researchers will gain access to Armenogram Turkish collections worldwide from a single platform; (ii) this open platform will allow users to add, edit, and revise records, serving as a basis for gathering statistical data; and (iii) high-quality master copies of digitized materials will ensure the long-term preservation of these fragile resources.

Yavuz Köse (University of Vienna) / Dilara Kaplan (University of Vienna)

Transcribing Armeno-Turkish Heritage with AI. Challenges & Opportunities

This paper presents preliminary results from a project that aims to automatically transcribe Armeno-Turkish texts into Latin script using the Transkribus platform. Two main objectives were pursued. First, a transcription model was trained on over 900 pages of Armeno-Turkish texts, primarily consisting of 19th- and early 20th-century literary material. The resulting character error rate (CER) was below 2%, indicating a transcription accuracy of approximately 98%. Second, a field model was developed to recognize the layout of Armeno-Turkish newspapers, as accurate text recognition is unattainable without it. In this context, effective layout recognition—essential for distinguishing articles, columns, and other structural elements—was also addressed. While the mean Average Precision (mAP) achieved exceeds 82%, which is a strong result, several challenges remain and will be explored in the presentation.

Jeanette Kilicci (University of Vienna) / Christoph Reuter (University of Vienna)

Armenian Congregations in Vienna: Preserving Cultural Heritage (360°)

In Vienna, two Armenian congregations are dedicated to the preservation of the cultural heritage of the local Armenian minority. These are the Mekhitharist Congregation and the Surp Hripsime Armenian Apostolic Congregation. The Mekhitharist Congregation is renowned for its magnificent Armenian Catholic church and its extensive library. The edifice was originally constructed between 1600 and 1603 as a Franciscan church but was subsequently rebuilt and completed in 1874. Conversely, the Surp Hripsime congregation serves as a pivotal hub for the Armenian community, offering educational opportunities in the Armenian language, music, dance, and religion through a Saturday school. Furthermore, the congregation owns a church on its premises, constructed in 1968 and refurbished approximately 10 years ago, which serves to meet the spiritual needs of the Armenian Apostolic community.

This research examines the pivotal role of both congregations in the preservation of Armenian cultural heritage in Vienna. In using 360° 3D cameras of the Department of Musicology, a virtual space will be created were interested parties will be able to tour both institutions and explore their extensive library, artefacts and artwork. The virtual experience will also showcase parts of Armenian liturgy and allow exploration of the significance of the church and cultural preservation in shaping the identity and heritage of the Armenian minority in Vienna by providing insights into the Armenian community.

Keynote Address

Sebouh Aslanian (Richard Hovannisian Endowed Chair in Modern Armenian History, UCLA)

Armeno-Turkish as a heterographic literary field: Complicating Ottoman Convivencia

This keynote presentation examines the complex cultural dynamics underlying Armeno-Turkish literary production in the Ottoman Empire through the analytical framework of convivencia versus conveniencia. Taking as its point of departure the "lachrymose" interpretative tradition exemplified by recent scholarship, this talk interrogates prevailing narratives of Armeno-Turkish cultural identity and literary hybridization. The presentation addresses a fundamental interpretative divide in Ottoman-Armenian studies. One scholarly tradition, influenced by the "lachrymose" conception of Armeno-Turkish historiography, characterizes Armeno-Turkish identity as the product of systematic and continuous oppression, with Christian populations living under the perpetual threat of annihilation—that is, a cultural formation born of repression rather than organic development. Conversely, another interpretative school posits Armeno-Turkish literary culture as evidence of an "inter-faith utopia," drawing parallels to medieval Iberian convivencia and citing the richness of composite cultural production as "proof" of harmonious coexistence among diverse religious communities. This presentation proposes a third analytical framework that acknowledges cultural hybridization while rejecting both the pessimistic lachrymosity and the idealized convivencia model. Rather than reflecting either systematic persecution or frictionless cultural exchange, Armeno-Turkish literary tradition emerges from this analysis as the product of a hierarchical imperial system organized around pragmatic accommodation—what Brian A. Catlos, Baki Tezcan, and others have termed the "principle of convenience" or conveniencia. This framework allows for a more nuanced understanding of how eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Ottoman Armenians and other "millet" communities navigated cultural production within the constraints and opportunities of imperial Constantinople's stratified social order.

Panel V: Sociolinguistics, Language, and Script Discourses

Çağdaş Acar (University of Chicago)

Armeno-Turkish: An Intersection Between Political and Linguistic Landscapes

Grammar books, especially when they are created as part of evangelizing missions, open windows into political, intellectual, and moral histories in addition to their importance as sources of philological study. Teaching grammar and helping students to gain speaking fluency in a language which is deemed to possess practical or spiritual value have always been imagined as instruments of larger projects such as sustaining religious institutions, training loyal subjects or establishing nations. Since they serve several purposes, grammar books have often been metaphorically called “gates” and “keys”. This paper intends to offer a close reading of grammar books in Armeno-Turkish and those intended for Armenian students to trace how the purposes to create grammar books for the Ottoman Armenian community change over time and how the use of Armeno-Turkish to teach Western Armenian and/or Ottoman Turkish contributes to the efforts of simplifying the Turkish language. Since the literature on the Turkish Language Reform epistemically excludes the intellectual efforts of non-Muslims and their use of Turkish in different alphabets (Armenian, Greek, Ladino, etc.), research in Armeno-Turkish grammar books, dictionaries, and other evangelizing production (such as the translations of the Bible) provides us with new lenses to approach political, intellectual, and moral histories of the Armenian community inside the Ottoman lands and to write a larger history of Turkish language simplification. A small corpus of Armeno-Turkish texts from 1720s to 1890s illustrates how they are both indicative of the political landscape and formative for the linguistic landscape for Ottoman Armenians. On the one hand, the vocabulary and the dialogues that are taught in these works reflect the immediate needs of their imagined readership. On the other hand, their authors and translators simplify Turkish and coin new terms to make sure that they can reach their readership. New Primer (Նոր Այբբենարան 1797, Trieste) and İlk Mektep Kitabı (an Armeno-Turkish primer, 1843, İzmir) are very selective in providing a “useful” vocabulary (moral, rural, and commercial) to its readers. In the post-1830 period when Catholic Armenians are recognized by the Ottoman State, it is striking how the Armeno-Turkish translation of the New Testament (1843, İzmir) makes a clear statement that they aim to write in “simple Turkish” (açık Türkçe) so that the message of Jesus is clearer. Agop Paşayan’s Miftāḥ-ü’l ‘Ulūm (1869) and Munteḫabāt-ü’l Munşe’āt’s (1871), however, represent the changing political landscape of the Tanzimat as Armenians are now taught the Ottoman rhetoric to better integrate to and navigate in the Ottoman bureaucratic and legal system. Grammar books, dictionaries and other evangelizing production in Armeno-Turkish offer an understudied corpus of primary sources:

- to better understand the political history of Ottoman Armenians – how they first use Turkish as an instrument to learn Western Armenian as a community and later shift their attention to mastering Turkish to better navigate in the Ottoman system as individuals.

- to complicate the history of language simplification in the Ottoman lands by extending the borders of an epistemically exclusive secondary literature.

Ozan Çömelekoğlu (Hacettepe University, Ankara)

“The Plaintiff is Lisan-ı Osmani”: A Debate Through Letters to the Editor Between Arakel Karamadtiosian and Hagop Pashayan

In December 1869, readers of Manzume-i Efkâr encountered an unusual public debate in the newspaper’s letters-to-the-editor section. The debate was initiated by Arakel Karamadtiosian, the author of Miftah-ı Kıraat-ı Huruf-ı Ermeniye fi Lisan-ı Osmanî. Karamadtiosian had demanded the immediate publication of his letter in Manzume-i Efkâr, in which he criticized several errors he claimed to have found in a recently released book titled Miftah-ül-Ülum by Hagop Pashayan. The theme of Miftah-ül-Ülum, like that of Karamadtiosian’s book, was learning to read. Both books were presented by their authors as essential guides to literacy. However, their audiences differed: Miftah-ı Kıraat was designed mainly for Ottoman notables seeking to learn the Armenian alphabet, while Miftah-ül-Ülum targeted Armenian children aiming to learn Ottoman Turkish. Hagop Pashayan did not remain silent when his work was publicly criticized; within a few days, he responded to Karamadtiosian’s letter in the same newspaper. Garabed Panosian, the editor of Manzume-i Efkâr, added a note immediately below Pashayan's letter, urging the disputants to conclude the debate: He stated that “after publishing the letters from both sides in the sake of justice, such mutual disputes would have no end.” Fortunately, neither Karamadtiosian nor Pashayan paid heed to Panosian’s request. Over the course of six letters published across seven issues of the newspaper, they engaged in a public debate on how to teach reading and writing Turkish using different alphabets.

In this presentation, I primarily aim to uncover the motivations of letter writers who came to prominence for their work on Turkish language education and the books they published on the subject during a period of growing literacy in the Ottoman Empire. Using the method of argument analysis, I explore their reasons for participating in the letters-to-the-editor section and what they hoped to achieve through their contributions. Additionally, I aim to highlight the opportunities provided by letters published in newspapers, one of the most under-researched areas of Ottoman journalism.

Hasmik Khalapyan (American University of Armenia)

Language, Nation, and Gender: The Role of Women in Shaping Armenian Linguistic Identity in the Late Ottoman Empire

This paper examines the central role that Armenian women played in the preservation and cultivation of the Armenian language, a key element of national identity and cultural continuity within the multilingual and multicultural context of the late Ottoman Empire. The paper addresses the following key question: How did Armenian reformers and intellectuals envision women's roles in language preservation, and how did women themselves respond to these expectations? Specifically, how did women's involvement in education and cultural life contribute to the national project of language preservation, and what challenges did they face in a society marked by linguistic and cultural diversity? Reformers and intellectuals viewed women, especially mothers and female educators, as the primary custodians of the Armenian language, holding them responsible for passing it down to future generations. They emphasized the importance of women educating their children in Armenian, ensuring that the language was preserved at home and in the community. At the same time, women’s own writings and activism reveal their agency in this process, demonstrating that women were not simply responding to nationalist demands, but were key players in shaping the discourse surrounding language preservation and its role in national identity. This paper draws on a variety of primary and archival sources, including periodicals, personal writings, and educational records, to explore how Armenian women navigated their roles as agents of language preservation. The study focuses on the tension between traditional domestic roles and women’s growing activism, particularly their efforts to balance motherhood with expanding roles as educators and public intellectuals. Women’s contributions to educational programs, literature, and the press helped shape how the Armenian language was valued and transmitted across generations.

The paper argues that the expectations placed on women were both a reflection of and a response to the national movement to protect and standardize the Armenian language as a cornerstone of the community's identity. Through a close analysis of periodicals such as Entanik, Tsaghik, and Hayrenik, the study highlights the evolving role of women in public debates about language reform and broader nationalist discourses. By examining the intersection of gender, education, and language, this paper asserts that women were not marginal figures in the creation of national identity; rather, they were central to the preservation and promotion of the Armenian language. Women’s work in maintaining linguistic purity, promoting language education, and reforming social norms surrounding language use was essential to the national project of language preservation. Ultimately, the findings emphasize the critical role of gender in the cultural and ideological politics of nationalism in the late Ottoman period.

Vahé Tachjian (Houshamadyan, Berlin)

Armeno-Turkish: A "Language with an Armenian Character" or Not? Reviewing Catholicos Papken’s Articles on the Use of Turkish as a Spoken and Written Language by Armenians

Catholicos Papken Gyuleserian, born in Ayntab to a Turkish-speaking family, authored several articles on the use of the Turkish language spoken and written (Armeno-Turkish) by Armenians. These writings span distinct historical periods: 1) the Hamidian reign, during which he served as the chief editor of the ecclesiastical review Լոյս [Light] (1905-1906, published in Istanbul); 2) the genocide period, with an article published in Fresno’s Նոր կեանք [New Life] newspaper in 1916; and 3) the post-genocide years, with two articles published in Սուրիահայ տարեցոյց [Syrian Armenian Almanach] in 1925 and Datev in 1929 (both in Aleppo). During the latter period, a campaign emerged against the use of Turkish by Armenians in major new diaspora centers like Beirut and Aleppo. While Catholicos Papken’s views on Turkish-speaking Armenians and Armeno-Turkish generally aligned with those of other Armenian intellectuals, they contained unique nuances shaped by his personal background. Turkish was his mother tongue, and he had translated works such as Nareg and other prayer books into Armeno-Turkish (Աղօթագիրք յատկապէս պատրաստուած թրքերէն խօսող հայոց համար [Prayer Book Specifically Prepared for Turkish-Speaking Armenians], Constantinople, 1899). Notably, in one of his articles, he described Armeno-Turkish as a "language with an Armenian character." Catholicos Papken’s writings provide valuable insights into the development of Armeno-Turkish among the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire. His explanations—or more precisely his justifications for Armenians’ use of the Turkish language—were significant. He notably argued that in the past times Turks would cut out the tongues of those who spoke Armenian, a claim that resonated with other Armenian intellectuals of his generation and has persisted as part of the Armenian historical narrative to this day. This lecture will present and analyze Papken's perspectives and the evolution of his stance on this linguistic issue across these historical periods. Besides Papken's published articles, I have access to the manuscript of his article published in Aleppo in 1929. This manuscript reveals that certain passages from earlier articles were self-censored. It is understandable that, in the post-genocide context, Catholicos Papken could no longer maintain the same level of tolerance towards this language, which was still both written and spoken by many Armenians.

Panel VI: Music Traditions

Jacob Olley (Cambridge University)

Armenian Transimperial Networks and the History of Music Printing in the Ottoman Empire

This paper will shed new light on the history of music printing in the Ottoman Empire by drawing attention to previously unstudied Armeno-Turkish sources and their social contexts. In existing scholarship, there is a widespread assumption that the first examples of Ottoman music in staff notation were published in the mid-1870s (Ekinci 2015; Paçacı 2010; Alaner 1986). However, an examination of Armeno-Turkish sources suggests that Armenian entrepreneurs began publishing Ottoman music considerably earlier. This paper therefore poses two interrelated research questions. Firstly, when were the earliest examples of Ottoman music in staff notation published? Secondly, how was the history of music printing in the Ottoman Empire shaped by the social conditions of the Armenian community and its transimperial networks? The paper will focus on primary sources held mainly in the library of the Mekhitarist Congregation of Vienna, the Bibliothèque national de France, and the British Library. These include two of the earliest known examples of Ottoman music in staff notation, published in serial form in Istanbul: K‘nar Arewelean (Oriental Lyre, 1858) and Ōsmanean Erazhshtut‘iwn (Ottoman Music, 1863). The paper will also provide a concise overview of other kinds of musical sources published in Armenian and Armeno-Turkish, including collections of vernacular song lyrics, opera librettos, periodicals, textbooks and treatises, and liturgical books.

In terms of methodology, the paper will combine empirical and interpretative approaches. It will establish a more accurate chronology of music printing in the Ottoman Empire and provide detailed documentation of the sources and their contents, including the lyrics of Armeno-Turkish songs and their transcription into staff notation. It will examine the economic aspects of music printing, such as publishing costs, prices, and subscription numbers. Furthermore, it will trace the networks of individuals, businesses, and institutions who interacted at different stages of production, distribution, and consumption of printed music. The paper will connect these issues to broader debates in Ottoman-Armenian cultural history, especially with regards to practices of transcription/translation, hybridity, and intercommunal relations (Charrière 2021; Aslanian 2016; Cankara 2015). In addition, it will consider parallel developments in Ottoman Greek music printing (Kallimopoulou 2023) and the relationship between music, print capitalism, and the tensions between discourses of imperial and national identity.

Preliminary research on this topic points towards a number of significant findings. Firstly, the beginnings of printed Ottoman music in staff notation are almost two decades earlier than currently supposed. Secondly, Armenian entrepreneurs played a key role in the emergence of music printing due to their technological skills, access to financial capital, and diverse social networks. Thirdly, intercommunal relations were an important factor in the development of commercial music printing, which drew on multiple linguistic and musical practices while also aiming to appeal to as many different readerships as possible. Fourthly, while Ottoman music printing was pioneered by Armenian entrepreneurs in Istanbul, it was supported by patrons and subscribers from a wide range of religious and linguistic backgrounds and locations beyond the imperial capital, including cities such as Izmir, Cairo, Paris, and Bombay.

Nejla Melike Atalay (University of Münster)

Armeno-Turkish Vocal Manuscripts in Ottoman Musical Heritage: Methodological Approaches and Challenges in the Critical Edition Process

The written heritage of the Ottoman Empire includes Turkish texts written in Armenian script, offering unique insights into its cultural diversity and linguistic interactions. This study focuses on a vocal manuscript selected from the Leon Hancıyan Collection in the TRT Archive, examining the methodological challenges and solutions encountered during the critical edition process. It aims to investigate the contributions of Armeno-Turkish manuscripts to Ottoman cultural heritage from both musicological and linguistic perspectives, while providing a methodological framework for future research.

The study addresses the following key questions:

- How does the use of standardized transliteration alphabets in musical editions impact phonetic accuracy and rhythmic integrity?

- How can challenges related to Armenian orthographic practices, such as those lacking functional relevance in Turkish or musical contexts, be resolved in the critical edition of Armeno-Turkish manuscripts?

- How do orthographic variations a;ect the representation of lyrics within their musical contexts?

- What methods can be applied to reconstruct texts that are aligned with their musical roles?

In the critical edition process, other Armeno-Turkish sources were consulted to fill gaps in the manuscript, ensuring a faithful representation of the text and its diacritic conventions while aligning it with the broader linguistic and musical practices of its period. These sources provided essential tools for understanding the musical structure and linguistic variations of the vocal pieces. The reconstruction of missing lines relied on comparisons with similar sources, and orthographic patterns were analyzed for compatibility with the musical context. Where necessary, textual elements were adapted to fit the musical framework. Additionally, another manuscript from the same collection, focused on the pronunciation of Turkish texts written in Armenian script, served as a key resource for linguistic analysis.

Arpi Vardumyan (Mesrop Mashtots Research Institute of Ancient Manuscripts, Yerevan)

Komitas Vardapet’s Armeno-Turkish Songs Manuscript

Armenian great composer Komitas Archimandrite (Soghomon Soghomonian) was born in 1869 in Kütahia. By the 19th century this town had become a significant artisan and cultural center with a majority Armenian population which, however, expressed itself mainly in Turkish language. Komitas writes in his autobiography that he was born in a musical family: his father and uncle were acclaimed church choristers (dpirk), who served for many years in Kütahia’s St. Theodoros Church. Naturally, they would take young Soghomon with them on Sundays and feasts, where he would demonstrate his elevated musical talent in grasping the niceties of Armenian ecclesiastical music and the finesse with which it was rendered. This elementary exposure prepared the way for his selection at age twelve, on his father’s death, to continue his education in Echmiadzin under the aegis of Catholicos Gevorg IV. As is well known, the latter was extremely moved to hear the boy sing the hymn Luys Zvart so perfectly though he was could not converse in Armenian at that time. Komitas’ parents were very cultural and had a special love of music, both in fact were not only performers, but also composed various songs. In his autobiography Komitas informs, that over the years 1892-93, during a visit to his birthplace, he recorded several songs in Turkish of their composition. The Charents Museum of Literature and Art in Yerevan has preserved a file (N352) containing sixty-six Turkish-language songs recorded in New Armenian Notation in 1892. Thirteen of these were published in Yerevan in European transcription in the 14th volume of Komitas’ complete works in 2006, edited by Robert Atayan. There, the musicologist remarks that the full publication of the collection of sixty-six songs with complete scientific apparatus was beyond the bounds of his present purpose, and best retained for a future comprehensive study. Judging from Komitas’ approach in this collection, he was already conversant with the techniques of ethnography during his student years. Thus, he meticulously dates his transcriptions and indicates the names of singers, among the twenty-two of which twenty-one were Armenians, most of them being members of his own family. As such, it is important to bear in mind that although the language of the collection is exclusively Turkish, one can observe significant affinities with Armenian musical traditions, especially the ashough or gousan genre of town music, as well as elements of popular and village songs. My paper will elucidate the Armeno-Turkish songs preserved in the Charents Museum archive and excluded from the final volume of Komitas’ complete works.

Jeanette Kilicci (University of Vienna) / Christoph Reuter (University of Vienna)

Exploring Intangible Cultural Heritage in Shared Folk Songs: A Comparative Perspective on Armenian and Turkish Traditions

Folk songs represent a paradigmatic instance of intangible cultural heritage, given that they are primarily transmitted orally within defined communities and regions. This oral transmission process serves to exemplify a dynamic and living cultural expression. The diverse versions of the selected (folk) songs shared between Armenians and Turks reflect the continuous evolution and adaptation of this intangible heritage as a living and evolving form of cultural expression, imbued with significant historical, social, and cultural value for the communities that practice it. Such practices reflect the unique identities, traditions, and values of the communities in question. The promotion of intercultural dialogue and understanding is facilitated by folk music, which thus contributes to the preservation and promotion of cultural diversity. What role do folk songs play in strengthening cultural memory and shaping intangible cultural heritage, especially in overcoming trauma within the Armenian diaspora?

This research presents an analysis of a selected set of folk songs that convey experiences of trauma within the Armenian diaspora. This study specifically investigates the role of these songs in fortifying cultural memory and shaping an intangible cultural heritage. The study compares the Turkish and Armenian versions of these songs among individuals from both communities residing in Vienna, with a particular focus on the Armenian minority. The methodology employed is interdisciplinary, integrating oral history, survey, physiological responses and linguistic analysis of lyrics as also an analysis of online comment sections under the selected songs. The shared melodies and partially overlapping lyrics of these folk songs facilitate the development of cultural memory, identity formation and the enrichment of cultural heritage among the Armenian diaspora. The findings will contribute to an understanding of the role of music as intangible cultural heritage as also the role in memory and trauma demonstrating the potential of music to also foster resilience, preserve cultural identity, and address shared trauma, including the elicitation of physical reactions during listening.

Panel VII: Printing Cultures and the Press

Hülya Eraslan (Ankara University)

The First Example of the Turkish Press with Armenian Letters in the Ottoman Empire: Takvim-i Vekayi

The first newspaper published by the state in the Ottoman Empire was Takvim-i Vekayi in 1831. This official newspaper, which was issued in accordance with the multiculturalism, multi-religiousness, and multilingualism of the Empire, was released in six distinct languages (Turkish, French, Persian, Greek, Arabic, and Armenian) and Turkish with Armenian letters. The subject of this paper is the examination of the Takvim-i Vekayi, printed in Turkish with Armenian script, published by the state immediately after the declaration of the Tanzimat Edict in 1839. The fact that the official newspaper was published in Armenian for the Armenian community in 1832, and Turkish with Armenian letters in 1839 can be considered as important data to understand the Turcophony of the Ottoman Armenian community. The Armenian-letter Turkish Takvim-i Vekayi is also the first example of newspapers and magazines that are considered to be Turkish press with Armenian-letter. In the studies on press history conducted to date, due to the lack of archival material of this multilingual official publication, only the Ottoman Turkish and French versions have been examined. These studies are also quite limited. Our knowledge of the issues of Takvim-i Vekayi published in other languages spoken by Ottoman subjects is not beyond a certain point, and no studies have yet been conducted on these issues. In the study, the first five issues of the Turkish version with Armenian letters, released for the first time in the Takvim-i Vekayi newspaper after the declaration of the Tanzimat Edict, will be examined with the historical and descriptive qualitative analysis method. During the examination, the early journalistic practices in the Empire—the identity of the reader, newspaper, and journalist—will be discussed, the press language of the period will be examined, and an attempt will be made to understand whether the acceptance of everyone among Ottoman subjects as equal citizens with the Tanzimat Edict played any role in the publication of Takvim-i Vekayi in Armenian-scripted Turkish. In the context of the Ottoman Armenian readership and public opinion debates, it will be considered why the Ottoman Empire needed a multilingual official publication, and the Ottoman Turkish editions of Takvim-i Vekayi of the same date will be compared with the Turkish with Armenian letters to reveal the similarities and differences between the newspapers. An answer will be sought to the question of why Takvim-i Vekayi, which was published in Armenian for the Ottoman Armenian community in 1832, was published seven years later in Turkish with Armenian letters. The similarity between the fact that Ceride-i Havadis, which was accepted as the semi-official newspaper of the state during a similar period, was also published in Turkish with Armenian letters as well as Ottoman Turkish, and who the Turcophone Armenian community consists of are among the issues of the study. Turkish with Armenian letter Takvim-i Vekayi, which is the subject of the study, is one of the oldest examples of the Turkish press with Armenian letters. As a result of archival studies of the editions that were not available in the libraries and archives of the United States, England, and Austria, the first five issues were reached.

Günil Özlem Ayaydın Cebe (Samsun University)

The Press and the Persona: Viçen Tilkiyan’s Self-Fashioning in Ottoman Print Capitalism

This paper examines the visibility and market strategies of Viçen Tilkiyan within Ottoman print culture, with a particular focus on his use of dual scripts, pseudonyms, and strategic engagement with press outlets and audiences. The central research question investigates how Tilkiyan negotiated the complexities of the Ottoman literary marketplace and how his economic and cultural capital shaped his literary identity. The empirical material comprises advertisements, reviews, and announcements in the broader Ottoman press. For example, Mecmuayı Havadis and Manzumei Efkâr allocated space for the announcements of Gülinya (1868), with the latter providing more comprehensive coverage over multiple issues. Letaif-i Asar not only announced the publication of Âşıkla Ma’şûk Dürbünü (1872, The Telescope of Love) but also satirically commented on it, blending humor with advertising. Tercüman-ı Hakikat and Vakit provide insight into the reception of Tilkiyan’s works including Sergüzeşt-i Mari Kraliçe ve Kızları (1878-1879, The Adventures of Queen Mary and Her Daughters), published under the name Esad. The study also incorporates booksellers’ catalogues, such as Arakel’s 1883 catalogue and the 1894 catalogue of Vatan Kütüphanesi, which list works like Sergüzeşt-i Kalyopi (1873, The Adventures of Kalyopi) and Zavallı Kızcağız (1874, The Miserable Girl), demonstrating the persistence of Tilkiyan’s literary presence in the market long after the works’ initial release. This investigation, to be developed through additional archival research, will reveal how Tilkiyan’s works were marketed, discussed, and critiqued across a variety of media.

This study further revisits Tilkiyan’s works, as part of the empirical corpus, emphasizing his conversational approach as an author who frequently addresses his readers in polemical pamphlets, prefaces, and footnotes. In these, he elucidates his efforts to enhance his visibility among the reading public, offering a unique glimpse into his self-presentation as a literary figure. The paper builds on newly discovered information about Tilkiyan in the print media, focusing on the discourse of announcements, advertisements, and the ways these shaped public perception of his works. By examining these overlooked dimensions, the paper provides a fresh perspective on works such as Çoban Kızlar (1876, 1877, The Shepherdesses), reinterpreting them with novel insights. It also introduces new material, such as his first print Şarkda Alafranga (1867, Westernism in the East), the missing preface page of Gülinya (1868), Garip Kız (1876, The Strange Girl), Madmazel Amber yahot Baloda Bir Vukuat (1878, Mademoiselle Amber or An Incident at the Ball), Yedi Dilberler (1881, Seven Beauties), and Misafir Abdal (1889, The Guest Dervish). The latter, in particular, is of interest due to its preface, which extends the span of Tilkiyan’s presence to 1889—eight years beyond the previously recorded period. Informed by insights gained from archival research, the paper will analyze the material in these texts, such as prefaces, footnotes, and commentary passages, to explore how Tilkiyan’s strategic self-presentation shaped his literary reception and visibility in the Ottoman print world.

Kübra Uygur (Brunel University London)

A Comparative Analysis of the Construction of Taste Through 19th-Century Armeno-Turkish and British Newspaper Advertisements

This study draws on Bourdieu's notion of taste and distinction and compares 19th century Ottoman Armenian and British newspaper advertisements to explore their role in shaping social hierarchies and consumer culture through the interplay of local and global influences. It examines how ideals of taste and distinction were constructed in advertisement texts, and how advertisers functioned as cultural intermediaries embedding symbolic value into goods and services. While advertising has long been recognised as a tool for reproducing social stratification in Western contexts, little is known about how similar processes unfolded in the Ottoman Empire. This research addresses that gap through a comparative analysis of advertisements from The Standard (1827–1916) and Illustrated London News (1842–2003) in Britain, and Manzume-i Efkâr (1866–1917) and Hayrenik (1879–1910) in Istanbul. The study employs qualitative thematic analysis on a sample of 400 issues spanning 1850–1900, revealing both overlapping strategies and divergent patterns in how advertisements sought to establish credibility, build symbolic capital, and shape consumer desire. British advertisements combined utility with aspirational messaging, increasingly targeting broader audiences with condensed and practical language. Ottoman Armenian advertisements, by contrast, retained a stronger emphasis on symbolic markers of distinction, frequently invoking European authority, language, and modern science to signal prestige and credibility. Despite differences in timing and sociocultural contexts, both sets of advertisements used endorsements, references to foreign expertise, and warnings against counterfeit goods to foster trust and frame products as legitimate and desirable. While British advertisements projected confidence in domestic production and imperial modernity, Ottoman Armenian advertisements constructed a more dependent cosmopolitanism, aligning goods with European sophistication to appeal to aspirational consumers in a transforming urban landscape. Through this comparative lens, the study illustrates the emergence of consumer cultures and advertising practices across two distinct yet interconnected imperial settings. It reveals how ideals of taste were shaped not only by local traditions and social positioning but also by transnational flows of goods, language, and symbolic value.

Samuel Chakmakjian (INALCA, Paris) / Onur Özsoy (Leibniz Centre General Linguistics, Berlin)

Word-final devoicing in Armeno-Turkish cookbooks

This study investigates orthographic and phonological patterns in Armeno-Turkish cookbooks, shedding light on an underexplored facet of the multilingual and multicultural linguistic heritage of the Ottoman Empire. We aim to identify patterns of orthographic alternation in Armeno-Turkish and examine their alignment with Modern Turkish, contributing to a deeper understanding of Ottoman linguistic practices and Turkish diachrony. Our corpus consists of cookbooks published in 1876, 1907 and 1926, sourced from the National Library of Armenia. Cookbooks offer a controlled register while revealing aspects of everyday language. Their shared vocabulary and recurring linguistic features offer a valuable snapshot of the interplay between Armenian orthography and Turkish phonology. Modern Standard Turkish orthography reflects regular word-final de-voicing in multisyllabic words (p, t, k) (Ketrez, 2016; Kopkallı, 1993; Tunçer and Sanıyar, 2022). However this aspect in Armeno-Turkish texts is not as consistent. To what extent do Armeno-Turkish texts demon-strate regularity or variation in voiced and voiceless obstruents, and what factors might account for these patterns? Preliminary findings reveal two key divergences from Modern Turkish orthographic conventions: (1) words consistently written with a word-final voiced obstruent (b, d, g – ex. şarab), and (2) words written with both voiced and voiceless obstruents in word-final position (ex. yemek; yemeg), varying even in the same text. Our findings demonstrate how Armeno-Turkish orthography regularly diverges from Modern Turkish, particularly in the representation of word-final obstruents. This variability reflects the interplay between Armenian orthographic conventions and Turkish phonology, offering new perspectives on past variants of spoken Turkish.

Panel VIII: Literary Genres

Azra Çelik (Boğaziçi University)

A Romance Translation in Armeno-Turkish: Hikâye-i Faris ve Vena – What Kind of Genre?

Long before the introduction of modern literature into the Ottoman geography in the 19th century, Eremya Çelebi Kömürciyan (1637-1695) produced a poetic translation in the romance genre: Hikâye-i Faris ve Vena. This text, written in the 17th century as a manuscript, was later printed and circulated by a printing press in the 19th century. There is no evidence of any previous work or translation in the romance genre before Hikâye-i Faris ve Vena in the Ottoman world. Furthermore, when considering the different translation practices over the centuries, it becomes evident that Kömürciyan expanded the text by adding sections typically associated with the “mesnevi” genre. The final part of the text, titled “Hateme tahsin medh düa nush u pend hamd u sena ve ismi mütercim beyanınde,” where Kömürciyan diverges from the norm, is particularly noteworthy. The aim of this paper is to argue that Kömürciyan’s deviation through the addition of this closing section—borrowed from another genre’s form, typically seen in Western romances—was intended to introduce the romance genre to the Ottoman world and influence its reception. Hikâye-i Faris ve Vena, as a romance translation that imitates the style of mesnevi and was later reprinted and circulated in the 19th century, represents an example of what Genette calls an imitation-text (pastiche). By modeling the style of the mesnevi genre, the translated text not only touches upon the romance genre but also approaches the mesnevi without fully belonging to either, thereby transforming into an independent example. The pastiche added by Kömürciyan shows how the stylistic imitation of the “mesnevi” within the romance genre was disrupted and generated new meanings, leading to a transformation that can be interpreted within its own production context.

Beyza Kaya (Boğaziçi University)

Hybridization of Literary Genres and Cross-Tradition Encounters in 19th-Century Literature

One of the distinctive features of 19th century Ottoman Literatures was that the literary public of the period began to resemble a “sphere of encounters”. There are five main dynamics underlying this sphere: